Pinotage

By Jamie Goode | 11th June 2018

It's every wine producing country's marketing dream: to have your own unique grape variety. These days the wine world is very competitive, and it's all very well making great Chardonnay, or Cabernet Sauvignon, or Merlot, or Sauvignon Blanc. Lots of countries make good examples of these wines, and you are just one of a crowd. What everyone wants is their own unique offering, and South Africa has just such a grape variety, and quite a bit of it. There is a problem, though. How do I put it kindly? This grape variety is not, to use a nice British phrase, everyone's cup of tea. It is Pinotage, until recently the marmite of red grape varieties.

It's every wine producing country's marketing dream: to have your own unique grape variety. These days the wine world is very competitive, and it's all very well making great Chardonnay, or Cabernet Sauvignon, or Merlot, or Sauvignon Blanc. Lots of countries make good examples of these wines, and you are just one of a crowd. What everyone wants is their own unique offering, and South Africa has just such a grape variety, and quite a bit of it. There is a problem, though. How do I put it kindly? This grape variety is not, to use a nice British phrase, everyone's cup of tea. It is Pinotage, until recently the marmite of red grape varieties.

The story behind Pinotage is an interesting one. It was first developed by a wine scientist, Professor Izak Perold, in the 1920s. Perold was a Professor at the University of Cape Town when he was sent overseas in order to collect grape varieties that might do well in South Africa. He came back with 177 different varieties, and was appointed as the first Professor of Viticulture at the University of Stellenbosch. As well as this collection, he was also interested in crossing grape varieties. Grape varieties don't normally reproduce sexually. They have all that they need to do this: their flowers contain both male and female bits, and the pollen from the stamens gets blown onto the anthers by wind (so the good news is that even if the disaster occurs and we lose bees, we'll still have wine). Then sex occurs and the ovules develop into seeds which are then surrounded by the grape berry. But new grape vines aren't produced by seed: if you tried growing one from seed you'd have a new variety. We like the varieties we have so we produce new vines that are genetically identical to the parent plant by taking cuttings. Small genetic mutations may occur in this process (this is what creates the different clones of each variety). But if new varieties are produced from seeds they are almost always less interesting than the starting varieties.

Perold wanted to beat these odds and produce a new variety. One of his crosses involved Cinsault (known misleadingly as Hermitage) and Pinot Noir, hence the name Pinotage. Now if you attempted this crossing again, you'd get a variety quite different to Pinotage, because of all the jumbling of the genes that happens during sex. But this particular crossing resulted in what we know now as Pinotage. But this new variety almost didn't make it. For some unknown reason Perold planted the seeds in his residence garden at the University in 1925. Two years later he left to work with the KWV, leaving the vines growing in his now untended garden. This new crossing was saved by a young lecturer Dr Charlie Niehaus when Perold's garden was cleared up, and the four plants were replanted in the nursery at Elsenburg Agricultural College by Prof CJ Theron, who later showed the vines, which he had grafted, to Perold. This was when the name Pinotage was coined, and gradually people began to plant it and make wines from it.

The reason the variety first came to be widely known is because of a wine made in the Bottelary Hills region of Stellenbosch by Bellevue. Their Pinotage won the award of champion wine at the Cape Young Wine Show in 1959, and in 1961 Kanonkop repeated the win with their Pinotage.

So what is the problem with Pinotage? There are a lot of people who are strong supporters of this variety, and there's even a Pinotage Association that seeks to promote it. Producers I speak to who make Pinotage say that it sells well, and some are even planting new Pinotage vineyards. This doesn't sound like a variety in decline.

But there are others who complain that Pinotage tastes a bit weird. They suggest that it has a very distinctive, slightly bitter, green streak that's easy to spot in blind tastings, often with a combination of sweet fruit and sourness in the same wine. There are sometimes distinctive herbal flavours, too. So is there something intrinsically bad – or evil – about this variety?

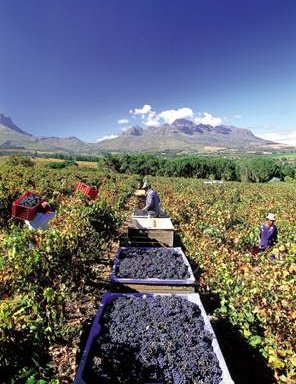

One of the issues with Pinotage is that it's quite difficult to handle in the vineyard. Its tendency is to produce bunches that have ripe grapes and unripe grapes in the same cluster. This sort of uneven ripening can result in some berries being very sweet and ripe at the time of harvest, while others are a bit green and herbaceous. The combination of sweet and sour characters in the final wine could be why some dislike Pinotage. In an effort to mitigate these ripeness differences, some producers are tempted to harvest very late so that even the less ripe berries are ripe, but this can result in big, rich, alcoholic reds that are then often bolstered with sweet new oak to create concoctions that some love, but which I find very hard to drink.

I used to be a Pinotage sceptic, but I've tasted some excellent ones, and the key to success starts with good viticulture: working with healthy vines, taking a modest crop, and being attentive during the growing season. Then it carries on by treating Pinotage more like Pinot Noir than Cabernet, choosing to make it in a lighter elegant style. After all, its parent varieties are both grapes that specialize in lighter, elegant, floral reds.

One of the most serious Pinotages of all is made by Kanonkop. Beyers Truter was the winemaker who put Kanonkop Pinotage on the map, and he's since continued the work with wines under his name. This is made very naturally from good, old vineyards and ages beautifully. His work has been continued by the current Kanonkop winemaker Abrie Beeslaar, who in addition to carrying on Beyers' legacy also makes an excellent Pinotage under his own label, Beeslaar. And more recently, Kanonkop introduced one of the country's most expensive, and best wines, the Kanonkop Black Label Pinotage.

Perhaps the most exciting Pinotage I have come across is made by David and Nadia Sadie. This is made in a very elegant, low extraction style that suits the variety perfectly. Until David and Nadia made this wine, Pinotage had been ignored by the new wave winemakers of the Swartland. Maybe more will be tempted to take a second look at Pinotage? Mick Craven and Craig Hawkins have made small volumes of an impressive Pinotage they labelled Clint. [There is a back story, yes.]

I've also enjoyed quite a few bottles of the Lanzerac Pinotage from the 1960s, all of which have been really enjoyable, and some of which have been very special. These bottles are easy to spot, with their distinctive skittle shape and vivid pink label. There are still a few around.

So, South Africa does have its own red variety, and although it has its detractors – and I'll admit I've tried a lot of horrible Pinotages in my time – there's nothing intrinsically wrong with this variety. If you find a bad one, blame bad viticulture and clumsy or rustic winemaking, not the variety. It's challenging, but when it's carefully grown and skilfully made, it can produce beauty.