The sweet wines of South Africa

By Jamie Goode | 3rd October 2019

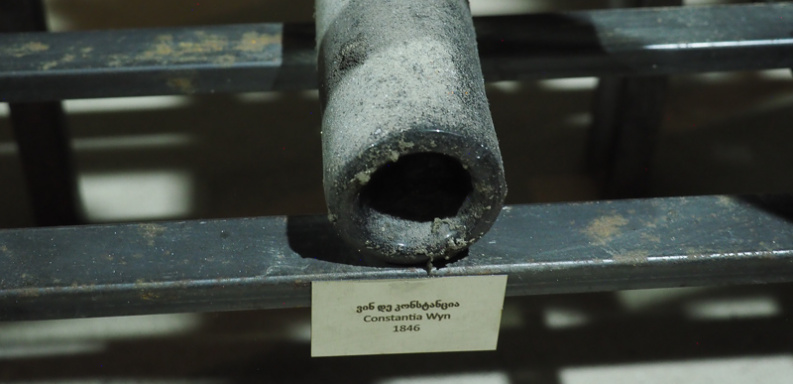

It was last week in Georgia that I came across the bottle that inspired this piece. I was in the old cellars of the Tsinandali Estate in the Kakheti region, where they had a collection of old wines, back to the mid-19th centuries. And their second oldest bottle was from South Africa: an 1846 wine from Constantia. I have no idea how it ended up here, in the private collection of Prince Alexander Chavchavadze. But here it was: an old sweet wine from the western Cape, which at the time was making wines famous enough to be collected by a Georgian aristocrat.

This was a time when people had much sweeter tastes, and sweet wines were revered as the ultimate expression of the vine. These days, they are less so, but South Africa has a very interesting heritage of sweet wines, which is currently undergoing something of a quiet revival.

Some of the credit here must go to Klein Constantia, who back in the 1980s revived a piece of vinous history. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Constantia was one of the world’s great sweet wines, but it disappeared with the phylloxera crisis in the late 19th century. Since 1986, though, the Klein Constantia winery has been making a sweet Constantia which they have labelled Vin de Constance. It’s based on the original wines that were made here, and which became famous in the 18th and 19th Centuries, only to disappear with the crises of the two mildews and phylloxera in the 1890s.

When the Jooste family bought the property in 1980, they were approached by a Stellenbosch Univeristy viticulturist, the late Professor Chris Orffer, who encouraged them to try to recreate the historical sweet wine. They agreed, Orffer helped them, and through the skill of the winemaker at the time, Ross Gower, they succeeded.

Many of the worlds famous sweet wines are either fortified (fermentation is stopped while there is still sugar in the must by the addition of spirit), or are made with the help of a fungus called Botrytis that attacks the already ripe grapes and concentrates the sugar and flavour (this is also known as ‘noble rot’). But the historical Constantia wine is made from allowing the grapes to stay on the vine a long time and achieve very high levels of sugar, in part through desiccation and raising of some of the berries, a process known as ‘late harvest’. It was likely made of a grape variety called Muscat. So, for the sake of historical accuracy, Vin de Constance is a late-harvest style made from Muscat without botrytis. This variety had disappeared from the vineyards, so it was replanted in 1982, and the first new era Constantia was the 1986 vintage, released in 1990.

Normally, late-harvest wines can be a little simple. So the winemaking team had to work out a special protocol for making a complex, world class late-harvest wine. First, 10% of the grapes are picked early, to make a base wine at 12.5–13 % alcohol with good acidity. Then they go and pick any already-raisined grapes. The remaining grapes are left to accumulate sugar, and leaf removal exposes the fruit to the sun, which helps more of them to raisin. Then, the big pick takes place in three passages through the vineyard. Altogether, around 10% of the crop will be raisins. The key stage is extracting the flavour and sugar from these shrivelled berries, and to do this some of the first-made base wine is used and the raisins slowly release their flavour. Then the skins are pressed quite hard, because tannins from the skins, normally a key part of red wine flavour rather than white, are important to the style. The wine then spends about four years in barrel until it is clear and ready to bottle. The result is a very complex, very sweet wine with astonishing ageing potential.

The original Constantia estate was huge, and a long time ago was split into a number of different properties. Since Klein Constantia released their Vin de Constance, neighbouring estates have joined the game: Groot Constantia followed in 2003 with their Grand Constance, and Buitenverwachting have their 1769.

On my last visit to Klein Constantia, as well as tasting the brilliant 2013 Vin de Constance, I got to try a bottle of the 1875 Constance, which was one of the last years of the sweet wine being made here before its production stopped. [It wasn’t because I was a special guest, it’s just that they already had an open bottle which a collector had brought along.] The team at the winery reckoned this wine was probably bottled in Europe from a barrel that had been shipped there, and they too the chance to analyse this piece of vinous history. It weighs in at 14.7% alcohol and had 220 g/litre of sugar. We sipped the small pour we were given in a state of humble appreciation. It had aromatics of leather, spices, old furniture, as well as raisins and table grapes with some honey, too. It was honeyed and smooth on the palate with real harmony, and notes of barley sugar, grapes, stewed raisins, bread pudding. Remarkable.

Another of the sweet wine champions of South Africa is Swartland winery Mullineux. Mullineux can’t claim any sort of Constantia-like historical connection – they are a relatively new winery – but they have made a focus on sweet wines from Chenin Blanc, and they’ve already released three sweet wines that count among the best sweet wines made globally. Their starting point is Chenin grapes with good levels of acidity, because it is acidity that really helps make a great sweet wine, providing balance for high sugar levels. Then they take these grapes and dry them out on straw mats in the shade of trees – it’s still quite warm here during harvest time. This drying process takes a couple of weeks, and is judged visually. The grapes shrink and raisin a bit, concentrating sugar, acid and flavour. Then they are pressed, and because they have shrivelled a bit this takes a couple of days (it would normally take three or four hours at most with regular grapes). The resulting must is incredibly rich in sugar, and even after fermentation, which stops at around 8% alcohol after struggling along for 8-10 months, there’s still around 360 g/litre of sugar, which is very high. The result, called ‘Straw Wine’, is powerful and complex with lovely acidity, showing incredible sweetness and flavours of marmalade, apricot, orange peel and raisins.

I should add here that Mullineux weren’t the first in South Africa to make a Straw Wine: that credit goes to De Trafford, whose excellent straw wine was first made in 1997, inspired by the Vins de Paille of the Northern Rhône in France. But Mullineux have taken things up a notch with their subsequent releases, both based on the straw wine technique. The first of these is Olerasay, a non-vintage wine. It’s a blend of straw wines from 2008-2014 kept in a solera fed by holding back two barrels each year. In a solera system the different vintages are mixed together: as older wine is removed, the new wine enters the system, in such a way that every bottle will contain a bit of every vintage, even the oldest one. This is another remarkable wine, with the ageing adding an extra dimension. The second is the super-expensive Mullineux Essence, first released in 2012. The wine is made from the very last ‘hard’ pressing of the straw wine grapes, which is incredibly rich in sugar and acidity – so much so, that fermentation took five years and then stopped at 4% alcohol. The remaining sugar level is 680 g/litre, the acidity an astonishing 15 g/litre and the resulting wine is bottled in 250 ml bottles and sells at over 1000 Rand a pop. It’s amazing.

Space doesn’t permit a full exploration of South Africa’s sweet wines, but as well as these superstars, there are also some other notable styles. Not least are the Muscadels or Muskadels. These are fortified sweet wines made from Muscat grapes (known locally as Muskadel), and they are fortified very soon after fermentation starts. They age brilliantly and are very affordable. I’ve had incredibly old versions from the KWV that have been quite stunning, and Nuy also make very good ones, including a delicious red version. And then there are the noble late harvest wines, which are made from botrytised grapes. This style is now widespread, consistently delicious, and worth looking out for.

Sweet wines may no longer be as popular as they once were, but in South Africa this is a healthy and growing category that has plenty to offer.